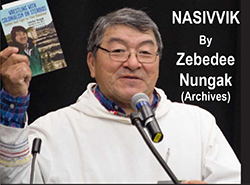

NASIVVIK By Zebedee Nungak,

Windspeaker Columnist; Archives 2004

Nasivvik is an Inuktitut word that means vantage point. It can be a height of land, a hummock of ice, or any place of elevation that affords observers a clear view of their surroundings to make good observations.

One of the strongest traditions of Inuit has been the preservation of culture through unikkaat (stories) and unikkaatuat (legends). A mere generation ago, most Inuit adults possessed the skill of storytelling, and retained impressive volumes of historical accounts and legends in their memory. Such skills were central to the maintenance of Inuit identity. Storytelling had served throughout the oft-mentioned "time immemorial" as a faithful record of happenings of importance to Inuit.

Qallunaat (white people) have often been amazed at the accuracy of Inuit accounts of events in history. Stories kept alive by oral transmission from generation to generation provided accurate accounts of Inuit contacts with Martin Frobisher in the 1570s, and with Henry Hudson's mutinous crew in 1611. The dates may not be specified in the Inuit versions, but the events, in their detail, have survived to be verified hundreds of years later with written records of the Qallunaat.

Since Inuit traditions are oral, and not literary, writing has seemed to be something for "others" to do. It was not at all an Inuit preoccupation in past times. It seems that Eskimos were neither meant, nor expected to be, writers. Thereby, non-Inuit have mainly served as go-betweens in delivering the riches of Inuit thought and folklore in written form to the non-Inuit world.

Here comes to mind part-Greenlandic Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen, whose name is synonymous with the collection and transmission of Inuit culture the world over. In more recent times, many Qallunaat have served as "enabling collaborators" for the few Inuit who have ventured into the world of publishing. Even so, exposure of writing by Inuit to the general public has yet to be fully developed.

Several Inuit have pioneered the literary trail as published authors, but the world of mainstream literature is still largely unconquered territory for Inuit. Inuit writers have yet to attain such "firsts" as making the best-seller lists or winning prizes for written works.

Over the years, I've encountered more than a few Inuit who were seriously into writing. One of them was a friend from school days in "the great land of the Qallunaat," who had maintained a daily journal for many years. He was about to develop his written material into a possible book when he had the great misfortune to lose his journals. Somehow, the pain of his loss planted a seed of determination within me to compile my own recollections of those years.

Then there was a young woman who had a pile of her deceased grandfather's diaries, who wanted to know how to turn them into published works. Not having a clue about whom to approach, I was not able to provide her with any guidance and felt terribly useless. These writings by a traditional Inuk were surely valuable, and deserving to be in print.

Several years ago, an Inuk man presented me with a manuscript written entirely in Inuktitut syllabics. The work's tidy order, in titled chapters, and its style of being written in verses, like in the Bible, was uniquely impressive. As a book detailing a way of life that is quickly fading into distant memory, it could've been a textbook for the study of Inuit culture. Properly edited and illustrated, this written work could easily make a run in mainstream literature.

With nobody actively seeking such material and bringing it to the attention of people who can cause such writings to become published, any number of journals, diaries, and manuscripts gather dust in many an obscure shelf.

Worse yet, stories lay unwritten by potential writers, never to bloom beyond the gleam in their writer's eye. This great, untapped resource has to become the primary preoccupation of people who can generate interest in and promote its development.

There are now so many Inuit organizations that one practically needs a written guide to keep track of their alphabet soup of acronyms. But, none of them serve in any way as an Inuit Writers' Union. I'm not advocating the creation of yet another organization just for the purpose of encouraging and supporting Inuit to get into writing. But until an Inuit-friendly publishing company is created, some organizations ought to get serious about activating support for Inuit writing without having to be begged.

Now, there's readily available support and funding for Inuit who are carvers, print-makers, throat chanters, drum dancers, and hunting, fishing, and travel guides. As a writer for the past few years, I've discovered there's not much ready assistance for Inuit with aspirations and talent in the field of writing, thereby stumbling upon a deficiency, which has to be given serious attention.

Ways and means have to be figured for Inuit writers to attain a presence in the world of letters and literature. Whether this can happen without people agitating for action remains to be seen.