Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Indigenous authors are feeling the love after being named 2021 recipients of Governor General Literary Awards presented by Canada Council for the Arts.

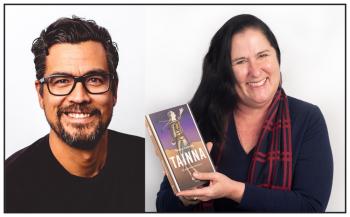

David Robertson, a member of the Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba, won in the Young People’s Literature—Illustrated Books category for On The Trapline. Norma Dunning, an Inuk writer who resides in Edmonton, won for Tainna: The Unseen Ones in the English Fiction category.

Winning was an emotional experience for both recipients.

“I had a few tears when I got the call,” Robertson said in an interview with Windspeaker.com. “I got a hug from my wife to calm me down a little bit. I was just really grateful, really thrilled.”

Dunning said the honour was especially meaningful in the first year of Mary May Simon’s appointment as Canada’s Governor General. Simon is also of Inuk descent and born in Quebec, like Dunning.

“I just broke down and cried,” Dunning added. “It was very unexpected for me.”

Robertson’s work, a 48-page picture book, documents a trip to a trapline by a young boy and his grandfather. The author drew inspiration for the book from his late father.

“In the end, it was a book that honoured my dad and our relationship as much as it was about the connection to land and community,” Robertson said.

For the book’s illustrations, Robertson chose Métis-Cree artist Julie Flett. They had previously worked together on When We Were Alone, which also won a Governor General’s Award in 2017.

“I told [my publisher] that the only person I wanted to do it with was Julie,” he said.

With Flett’s father also going through health struggles during the book’s production, Robertson said the pair had a strong bond as they worked together.

“We were both kind of doing it with our dads in mind,” Robertson said.

Robertson has experience writing graphic novels and other full length works, but says that condensing his work into a picture book was actually a challenge.

“Every word has to be perfect,” he said.

“In a way, this book is very close to non-fiction,” he added. “But it's finding that level of emotional honesty. It's laying yourself bare in a way. You have to give up yourself in a story like this, because it's so personal, and you have to be able to mix the elements of fiction that you've used in a really seamless way.”

Robertson hopes that his books can be used as an educational tool as part of the reconciliation process.

“It's not all about trauma,” he said. “It's about language. It's about community. It's about the beauty of the way that we live and the way that we have lived in the way that we continue to live.”

Robertson said the feedback from readers has shown him the book has made a positive impact.

“I want to do whatever I can to try and help people, he said. “I don't want to just write stories with my work. I want to create change.”

Dunning wrote six short stories in Tainna that are centred on the experiences of modern-day Inuk characters as they deal with alienation, displacement and loneliness.

She said there was no linear path from start to finish for her work.

“I'm not a very disciplined writer. I sit on [my ideas] for a very long time to percolate inside of me and then I'm able to put it down on paper,” Dunning said, though she did try to block off a few hours every weekend to sit and hammer out the manuscript of Tainna, pronounced Da-e-nn-a.

“If you get a couple of hours of good writing. That's like four days of bad writing,” Dunning said with a laugh.

Like Robertson, Dunning drew on lived experiences, but feels like readers are more willing to accept non-fiction versions of traumatic events.

“To me, the stories give mainstream and anybody time to think about things like colonialism and assimilation and racism and all the things we think have gone past. They're very much alive and well in Canada,” she said.

Dunning said her stories “arrive very quickly” to her.

“I don't sit down and think I know I'm going to write a story about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls,” she said. “I see the characters, and then I begin to write that story.”

Currently working as a lecturer in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Education, Dunning said her writing helps keep her grounded in her professional career.

“It's one thing to lecture. It's quite another thing to write,’ Dunning said. “I need to have that creative [line of work] in order to do the academic [work].”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.