Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

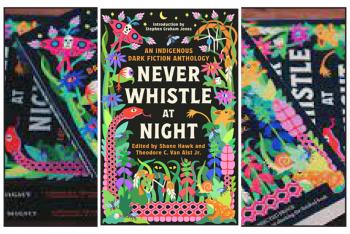

Gatekeepers, says Shane Hawk, co-editor of the dark fiction anthology Never Whistle at Night, are one reason why Indigenous writers have only broken into the horror genre in the last decade or so.

“I think it's a marketability thing where there’s been historically gatekeepers who have allowed who can be published,” said Hawk.

“I think now more people are seeing that, ‘hey, Indigenous people can write genre as well’,” says Hawk, who calls San Diego home.

He and co-editor Theodore G. Van Alst Jr. were in the position of gatekeepers in 2021 when they put out an open call for emerging Indigenous writers to submit something “dark and scary.” Hawk admits he didn’t know what kind of response they would get, and they had a hard time selecting from the more than 100 submissions received.

Understanding that to make an anthology marketable the editors would need recognizable Indigenous authors, Hawk started emailing and direct messaging “a bunch of writers and asking.”

The first author he reached out to was fellow Cheyenne-Arapaho tribe member Tommy Orange, whose initial novel, There There was finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize. Orange agreed to contribute and his short story “Capgras” is part of the final selection of 26 stories for Never Whistle at Night.

“Pretty much” every established author agreed to write a piece for the collection, says Hawk, and those submissions were balanced with work from emerging writers. Hawk and Van Alst each wrote a short story as well.

The forward is written by Blackfeet Tribe member Stephen Graham Jones, author of The Only Good Indians, a horror novel that won the Ray Bradbury Prize for Science Fiction, Fantasy & Speculative Fiction in 2020.

“We wanted to get new names out there and increase the field of Indigenous dark fiction,” said Hawk, but it wasn’t a vision that came without a battle.

Reaching out to the Big Five publishing houses, Hawk and Van Alst were told by one that the entire anthology, with the exception of a sole emerging writer, needed to be made up of established Indigenous authors.

That didn’t fit the editors’ mission.

They got the response they wanted from Vintage Books, Penguin Random House Canada’s division in the United States.

“She was so sweet,” said Hawk of Vintage editor Anna Kaufman, who pushed the story count for emerging writers from seven to 12 for the anthology.

Authors from both the U.S. and Canada are part of the collection, which hit the bookshelves late last year. The hope had been to include Indigenous writers from beyond Turtle Island, but there were legal limitations.

That didn’t mean the title of the anthology couldn’t be global.

“When Ted and I were trying to put this together and just brainstorming…we were really thinking, ‘OK, what's a title that can really speak to a lot of people that would be widespread’?” said Hawk.

Van Alst suggested Never Whistle at Night noting that tribes across North America, Asia and Australia believe that bad things are conjured when that action is taken.

And cautionary titles, says Hawk, are some of their favourite titles for horror movies.

“In horror it's shaped around something that happens, something that you do in action and then a consequence,” he explained.

Hawk’s short story, “Behind Colin’s Eyes,” is one of the submissions that tackles whistling at night and the consequences. It wasn’t the first story he wrote for the collection though. When he shared the first story with his grandmother, she “hinted” at keeping that story in the family. So he put whistling within the narrative of a new story he crafted, which was also part of his own family lore.

The eerie atmosphere and the ominous ending of “Behind Colin’s Eyes” are part of the tension that makes a great horror story. Hawk further explains that horror stories involve three elements: tension, horror and then terror.

“If you try to have all three of those elements within your horror story, it really hits everything that human beings crave from a story, especially from a type that's a little darker, and I try to do that with my story ‘Behind Colin’s Eyes,’” he said.

However, more than that, “Behind Colin’s Eyes” (with the last two words read as the singular “colonize”) is one of a number of submissions that reflect on colonization, whether it’s blood quantum, residential schools or loss of culture.

Hawk says it didn’t surprise him that so much of the dark fiction took up that theme.

“I think it's just something all of us Natives think about almost daily. Not every single day, but it's there. We're still in colonial systems. We're still talking about decolonization. If it'll ever happen. And it's there. It's like part of us, which is sad in a way, but through fiction, through art, I think we can make changes,” he said.

The horror in this collection of dark fiction isn’t all due to wheetagos or aliens or little people or other supernatural beings.

“I think all the horrible things that we can conjure up supernaturally, human beings have done more or worse…Those (stories) definitely freak me out a lot more, whether it be natural disasters or people turning on you or they’re not who they said they were. These heinous, awful things that human beings are able to do and have done throughout history,” said Hawk.

Hawk, a history teacher, came by his love of reading and writing horror fiction only since 2016.

“I've always been a fan of horror movies. I can't really explain why. I just think I like the rush of being in my own living room and experiencing the craziest things on screen, but still being safe,” he said.

As for writing horror, he says he finds it cathartic and therapeutic.

“I like to be able to enter spaces where I can use for sort of a vehicle to criticize and make social commentary on things…It’s just fun to me. I mean, because I get to bring my love of horror and just things that creep people out and then bring it into exciting narratives where people can get more than just spilled blood or knives or, you know, crazy things. They can take more from it,” he said.

And “more from it” is what Hawk hopes non-Indigenous readers get from the anthology. They need to see the stories as more than “just white people (are) bad, Indigenous people (are) good.”

“We have all these serious, real-life themes and I hope that (non-Indigenous people) start to maybe research and maybe ask around, try to learn what past and present issues are plaguing Indigenous people,” he said.

As for Indigenous writers, he wants them to understand they are no longer relegated to writing historical fiction or memoirs or literary work.

“There’s some amazing Indigenous literature,” said Hawk, but horror is a genre that can also be embraced by Indigenous writers as one of the “multitude of things that we can still do. They just have to really hold on to hope… and, looking at the future, see that ‘Hey, this is just the beginning’…And I think a lot of people—actually when I say ‘people,’ I say ‘the market,’ I say ‘readers’—are open to that sort of thing when they probably weren't like 15 or more years ago.”

Never Whistle at Night can be purchased online at https://www.amazon.ca/Never-Whistle-Night-Indigenous-Settled-ebook/dp/B0BZ3J6JT4

Support Independent Journalism. SUPPORT US!