Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

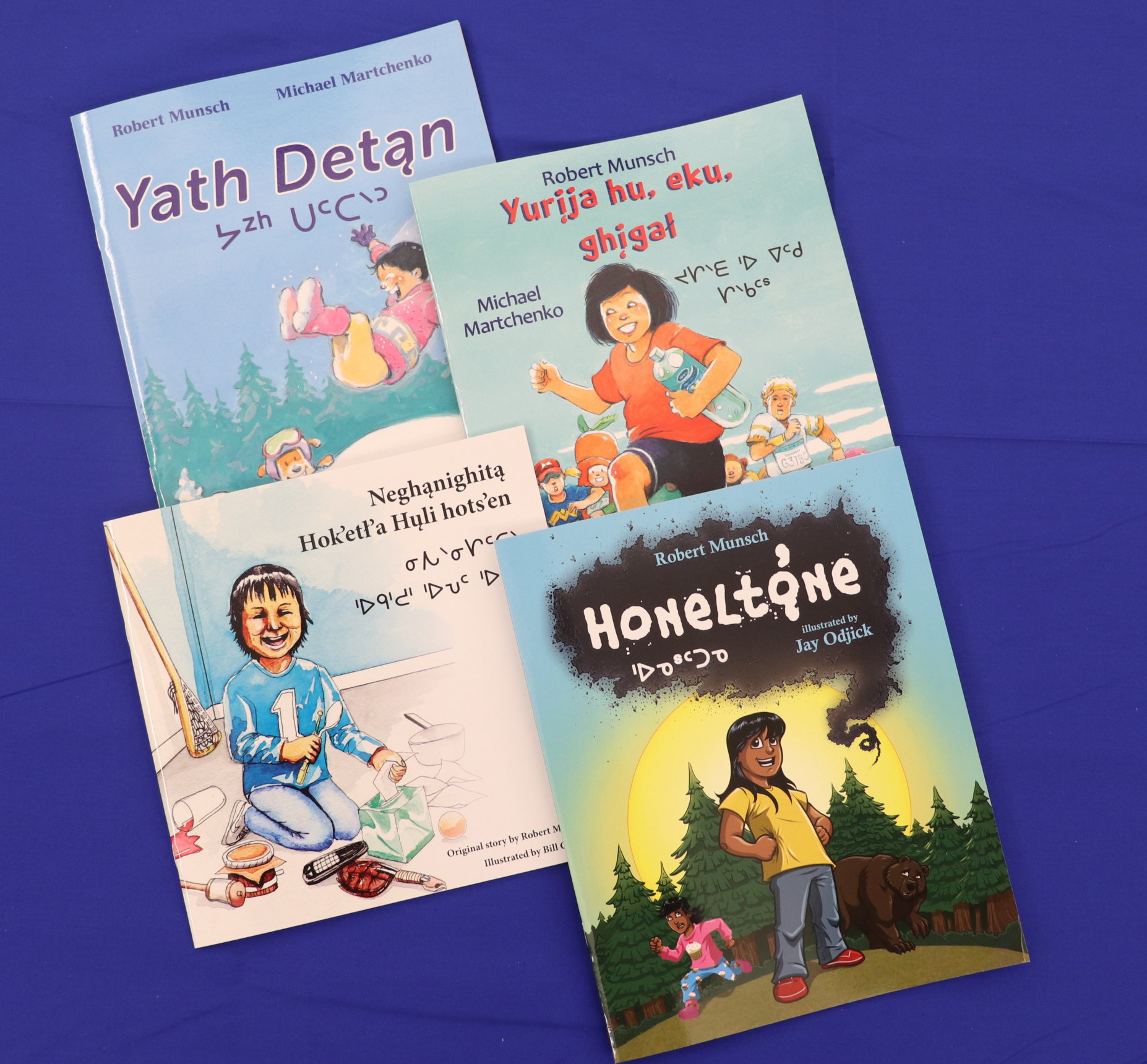

Translating a selection of well-loved Robert Munsch books into nêhiyawêwin (Cree) and denesųłıné (Dene) caps off a two-year project undertaken by University nuxełhot’įne thaaɁehots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ) to help revitalize Indigenous languages.

Four books were translated into both languages, including audio recordings: Love You Forever; Ready, Set, Go; Blackflies; and Deep Snow. Also translated into nêhiyawêwin was Smelly Socks.

Lynda Minoose is one of the translators. She’s been working as the language and culture director for Cold Lake First Nations since 2010 and has done a lot of translation work for UnBQ. She says translating is a lot of work, but also a good learning experience for her.

“I don’t see it as work, I see it as a learning opportunity. I learn fluency for one thing and how to correctly say things. I learn how to read and write, how to talk, how to share. I learn the correct nuances of our language.”

Minoose’s worked on Love You Forever and Deep Snow and hers is the voice reading the stories in both recordings and singing the mother’s song in Love You Forever.

Hearing the stories read in these languages is a rewarding experience, said Tina Wellman, language resource developer at UnBQ.

“You can tell a story or a joke in English and it’s so bland, but then you go and say it in Cree and you’ll have a room full of laughter. It’s such a descriptive language.”

Wellman discovered that Munsch is a big advocate of Indigenous language use. She contacted publishers Firefliy and Scholastic about how to go about translating the books after doing some research. She then approached Dr. Marilyn Shirt, language team lead at UnBQ, about undertaking the translation project. They then had to find funding, which was provided through an Alberta Education Indigenous languages grant.

Wellman started the translation project by purchasing a number of the Munsh books in English “to take a look at which ones have the illustrations that would depict us best.”

Blackflies was originally published with illustrations from First Nations artist Jay Odjick of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation in Quebec. He congratulated the team on their work in a Facebook post.

“Tremendously happy to share the news that Blackflies, my collaboration with Robert Munsch, has been translated into Cree by Susan Dion, transcribed into syllabics by Tina Wellman and Dene, translated and transcribed into syllabics by John Janvier!... My hats off to everyone involved and my gratitude and respect for them for fighting for our languages and youth. Kichi Migwech,” he wrote.

“It’s a dream of mine that someday parents will be able to have libraries for themselves and their children in Indigenous languages.”

Blackflies was a huge success, as are all the Munsch’s works.

“Everyone’s heard of Robert Munsch and a lot of our kids have read them,” Wellman said. “I’m a big advocate of our language and I wanted to reach our young parents and their children. I can only speak for myself, but I grew up in a family where the words were said ‘What is our language worth?’ So, we weren’t encouraged to speak our language.”

Shirt interpreted the question. “The way I would translate that is ‘What is the use of our language?’ In that context (Wellman’s) mother was saying ‘It’s not of any use to us’.

“One of the reasons we lost our language is some parents asked how is it going to benefit our kids to learn and speak Cree? It’s better for them to learn English so that they can function in this environment. And then some parents said ‘It is better for our kids to learn English so they don’t suffer the pain of what we suffered when we were going to school, and the discrimination and the difficulties we had and the abuse as a result of speaking Cree’.”

The loss of Indigenous language use is the reason Wellman thought the audio component would be important because there are so many individuals unable to read and write in the languages and she wanted to grab that audience.

Shirt said she spoke Cree until about the age of five or six and then went to boarding school and her mother decided it would be best for the family to speak English. Shirt began learning the language again as an adult after her daughter was born. She and her husband wanted to create an environment for her daughter to learn Cree.

Language revitalization has developed into Wellman’s passion.

“I started my journey working in group homes and I saw the kids there not knowing the language, so I thought I would go into the social work program and change policies and make sure our language was being taught to the kids in care.”

Once in the program at UnBQ, all Wellman could think about was language, so she switched her area of study and learned how to read and write in nêhiyawêwin because, although she was fluent speaking it, she had never learned to read or write it.

“And that got me more excited about it because I’m a bookworm and I want to be able to go to the bookstore and grab a book in nêhiyawêwin and be able to read it.”

The two-year project included more than translating the Munsch books. Resource kits were created for teachers, which include lesson plans, videos, games and 14 story books written by UnBQ students.

“We have students in our classes who write their own stories and then we publish those,” Shirt said. “I think that there are enough stories that people have within our own communities, our own history and our own life events that we need to tell for ourselves.”

Shirt said they realized there is a lack of resources in Indigenous languages at all levels: tertiary education, secondary school, and for people to be able to watch media or read books.

“And the focus [usually] isn’t on our own stories, our own dreams. It’s somebody else's: Jack and Jill and that life. So I think we need to be able to have value in our own stories, our own life and our own history,” Shirt said.

“From the time of (Prime Minister John A.) Macdonald, there was the development of a negative Indian narrative that enabled people at that time to treat First Nation people with the callousness that they did. So that allowed the population of Canada to accept that kind of behaviour, but it also affected how we viewed ourselves because we were also listening to that negative Indian narrative,” Shirt said.

“So that has to change. We have to start seeing value in our lives. And the stories that the students have been writing about things they have experienced in their own lives are not all negative. They’re quite positive and they show us as human beings. And if those stories can be told in Cree, so much the better. Or in denesųłıné.”

Visit https://www.bluequills.ca/UnBQResources/BQStore to order the books and resource materials.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.