Image Caption

Summary

By Andrea Smith

Windspeaker.com Contributor

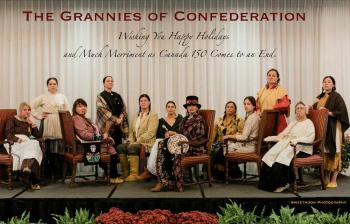

Three Canadian professors, who feel strongly about the role of Indigenous women in Confederation, have recreated a famous painting.

The “Grannies of Confederation” photo is an image of Indigenous women and how they would have looked at the time of the Confederation of Canada, and is cast in the image of the famous “Fathers of Confederation” painting.

The point is to shed light on how Indigenous women have been largely left out of the Confederation narrative and Canadian history thereafter, too.

“This came about because Kim (Anderson) was on the organizing committee for the Canada 150 conference at the University of Guelph, and being three Indigenous women, we thought there needed to be some Indigenous content….

“We organized a whole panel surrounding a sort of Indigenous resistance to Canada 150,” said Dr. Lianne Leddy, program coordinator and assistant professor of Indigenous Studies at Wilfred Laurier University.

Anderson of the University of Guelph and Dr. Brittany Luby, also of the University of Guelph, worked with Leddy on facilitating the conference and the photo. Together, the three form a performance group called the Kika-Ige Historical Society.

“Part of the conference was to commemorate the Canadian Confederation, and as Indigenous women we feel that it silences our voices as Indigenous peoples, and it silences our sovereignty and our own histories that date back much further than Confederation,” said Leddy.

The original “Fathers of Confederation” painting was done in 1884 by Robert Harris. It was lost in a fire in 1916, and recreated by Rex Woods in 1969. The painting depicts two major conferences, both of which are believed to have laid the groundwork for the Confederation of Canada—the Charlottetown Conference and the Quebec Conference.

There are 33 prominent politicians from the time in it, and one political secretary—all European, and all men. Dr. Anderson, Dr. Luby, and Dr. Leddy, enlisted the help of other Indigenous faculty and staff at University of Guelph, so they could match the number of “Grannies” with the number of “Fathers.”

The Indigenous resistance panel Leddy is referring to is the photograph itself, as well as a series of talks. They also put on a significant performance as the conference was opening; The women in their historic clothing, stood stone-faced by tables as guests arrived and seated themselves. The expressionless behavior was intentional and helped to drive home their point, said Leddy.

“We stood there as part of a performance just to make people uncomfortable. To insert our presence there in a way that was unexpected, that people would have to contend with us at this conference. The picture was part of a larger process there to question our ideas about what Canada 150 means to Indigenous people,” she said.

According to Anderson, the term Kika’Ige, which became the name of the historical society she is now part of, was shared with her by Ojibwe Elder Rene Meshake. Meshake’s father was a firefighter who would go into the woods, find the fire, then mark a trail on his way back to the community by chipping pieces off of trees with his axe. He once told Anderson he could see what she was doing in the world of academia was similar, in that she was also “chipping off bark” and “blazing a trail for students and travellers.”

In a video shared by Anderson (available on Youtube; see “Canadian Conversations”), she talks about the reason Kika’Ige came into being two years ago. Wilfred Laurier University planned to erect 22 statues of past prime ministers. Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. McDonald, was the first to go up. Anderson and her colleague, Dr. Leddy, were angered by this, because of the sad truth of McDonald’s manipulative and malicious tactics with Aboriginal people.

Anderson and Leddy dressed in prisoner’s uniforms and sat beneath the Sir John A. McDonald statue, in chairs which were part of the new installation. They sat for days, in quiet protest, being joined at one point by Anderson’s violinist son, who added music to their display.

Halloween then rolled around and they even handed out candy along with tidbits of tragic truth on paper, which said, “McDonald’s government used rations to subjugate and control Indigenous communities.”

In the video, Anderson explains, “It was me and my colleague, Lianne. Two Native women with PhDs… Not the kind of Indians Sir John A. had in mind when he hung our leaders and put our children in residential schools.”

In the video, she burns sage and continues to say, “Grandfathers forgive our dark humour, for we are mindful of all the Indigenous men who fill the jails today. Nimishomis (my grandfather), Big Bear and Poundmaker. Nimishomis, who protected the starving and impoverished. Nimishomis, who suffered the cold seats of Stoney Mountain Prison at the hands of Sir John A. McDonald. Nimishomis, who were not part of the conversation.”

Anderson and Leddy—along with the countless others who supported them—were successful in their protest, and the statue was relocated. This was the first act performed by Kika’Ige. The resistance conference along with the “Grannies” photograph was the second.

The “Grannies” official photographer was Tenille Campbell of Sweetmoon photography. She is a friend of Dr. Brittany Luby, and was more than happy to be involved.

“I felt really thankful to be a part of the group. I saw what they were doing and what kind of work had gone into it, in acting it out… for them to not smile and not welcome people I think was pushing the limits. And to see people’s faces drop from smiling to uncomfortable… it was very powerful,” said Campbell.