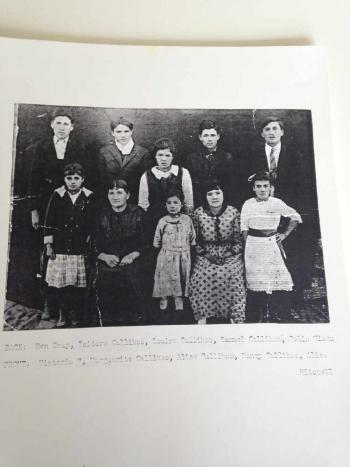

Image Caption

By Andrea Smith

Windspeaker.com Contributor

EDMONTON

Members of a First Nation in Alberta are seeking reparation from the federal government, which does not official recognize the nation’s existence.

The Michel First Nation was dissolved completely in 1958, and about 750 members now sit on a “general membership list,” a list of people who are recognized as having Indian status, but who have no nation to which to associate them.

The people have been working to be recognized for years, and recently enlisted the help of Kim Beaudin, national vice-chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, to push their agenda further.

“One of the things that happened in 2008 was the federal government said the band didn’t exist and the people did not exist, and no treaty was ever signed,” said Beaudin, referring to a court ruling which came from a case the Michel people had previously brought before court.

“I found that quite interesting… When in fact you have hundreds and hundreds of people who have general membership status… And 90 per cent of people who sit on that list in Alberta are descendants of Michel and Callihoo (Callious) bands. That’s quite significant actually,” he said.

According to Beaudin, (and the Michel First Nation website), the reserve was located on a 40- square mile plot located northwest of Edmonton, along the Sturgeon River, and near the St. Albert Indian Residential School (St. Albert Mission).

Michel officially entered Treaty Six in 1876, and was recognized by the Crown, a few years later. The First Nation “enfranchised” completely in March 1958, with government officials at the time citing all the members legally signed off on their Indian status in exchange for land and monetary benefit.

Beaudin is not convinced it was a completely fair and above board deal, particularly after hearing from past members and descendants of members, including his own mother.

“My mother turns 80 here in a week, and she didn’t get anything… My mom didn’t get anything. Her mother didn’t get anything. Her grandparents didn’t get anything. She couldn’t understand how her cousin got money... She doesn’t know why, (but) certain people did,” he said.

Beaudin has had meetings with current members recently in Edmonton, as well as a meeting with Alberta Minister of Indigenous Relations, Richard Feehan. Beaudin is planning another meeting for Aug. 19, and is hopeful more government officials will attend.

“What’s our main objective? We want to repatriate the people of the Michel. They still do have chunks of reserve land there. I found out, you can’t sell grave sites. And the Alexander Reserve and Maskwacis took some of that land… Even a cleaning lady who worked for INAC was given land,” he said.

Linda Buffalo is a direct descendant of Louise Callihoo, a member of the Michel First Nation, at the time it was dissolved. Buffalo and Beaudin are actually related. Their grandmothers are sisters. It was a surprise to them when they first started talking at a Michel Band meeting a few years ago.

Buffalo has spent nearly three decades researching the history of her family. When she was in her early 20s, she went directly to Ottawa herself to ask the Department of Indian Affairs for records that would help her unlock significant pieces of her own life puzzle.

“My grandmother was one of the four women that never left…. She remained Treaty. That’s when they started the general list everybody sits on today,” said Buffalo, explaining what she found out then. “The reason why they never sold is they were deemed mentally incompetent,” she said.

Buffalo’s grandmother was one of four women the government of Canada, and the Department of Indian Affairs, said was “incompetent,” and therefore could not sign to enfranchise. Instead these ladies were disregarded altogether, she says.

“The four women didn’t get anything, except their five bucks a year,” she said, adding that at time she experienced conflict because she was told she needed to have an official letter from her band before she could access any records.

After telling them she was a “general member,” the government officials deliberated for four days, then handed over what she was looking for.

“I, also, in some of my research came across that there was a man who was ‘incompetent,’ and he was on the list where they weren’t going to let him go (enfranchise). And then he got swiped off the list, and he got land and shares,” she said.

Buffalo is referring to shares in a company called Michel Investments, which was started up immediately after the First Nation was dissolved. Buffalo is suspicious regarding the treatment of the four “incompetent” women and wonders why the only “incompetent” male was still able to participate in the enfranchisement.

Buffalo even once took it upon herself to phone the investment company, an experience which left her rattled.

“Years ago, I called them up, and said ‘I’m just wondering about my grandmother. This is her name… does she have anything to do with this company?’ They called me a gold digger, and said ‘Don’t you call back here.’ I got off the phone and I was crying. I was just a young girl then looking into something for my mom,” said Buffalo.

She, and many of her family members—including her mother—were able to have general membership status given to them in 1985, a result of Bill C-31 being passed. This is when many of the other current members also received that status. But it's a wonder to Buffalo why her grandmother was even placed on the general membership list.

“Every time I start talking about it, it does work me up… over the last 30 years. I start getting so pissed off because I just think they took everything away from us. I grew up wondering where we came from... It’s sad what they did,” she said.