Image Caption

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Indigenous filmmaker Stephanie Joline’s newest documentary, I Place You Into The Fire, features Mi’kmaq spoken word poet Rebecca Thomas of Lennox Island First Nation.

Thomas once served as Halifax's poet laureate. The award-winning poet also works in Aboriginal Student Services at Nova Scotia Community College.

Combining poetry and visual art, Joline works with Thomas to use personal storytelling as an entry point into the larger themes of intergenerational impacts of colonialism, reconciliation and healing.

When Joline approached her with the documentary idea, Thomas was reluctant at first.

“I think that there are people out there doing far cooler things than I am. I don't feel remarkable enough to have been the subject of a documentary,” she said.

That humility translates into the warm, conversational tone in I Place You Into The Fire, where the viewer feels they are sitting in Thomas’ kitchen keeping her company while she makes homemade mayonnaise.

That friendly intimacy is how audiences learn about the impacts of residential school, colonialism and the injustice that Indigenous people continue to face. Audiences also learn about Thomas’ own family story with that injustice and how she has learned to move forward.

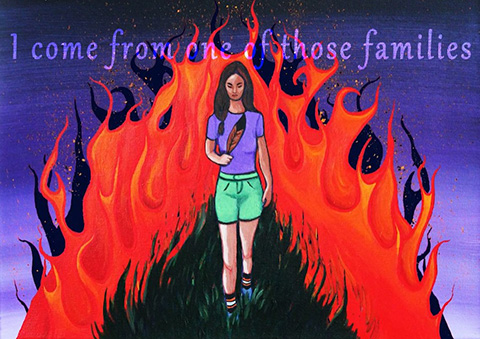

I come from one of those families where promises were broken, where hurt was endured, but never spoken, I come from one of those families where we solved our problems with our fists, but ended every night with a hug and a kiss, Thomas shares with her poetry.

The journey of unlearning and learning is a consistent theme through the film.

“I liked that idea of not perpetuating a system,” Thomas said. “And you know, we talk about generational trauma all the time in our communities and it's a really big honour and responsibility to have that trauma stop with me.”

Thomas said there are three similarly shaped words in Mi’kmaw that have drastically different meanings: kesalul means “I love you”; kesa’lul means “I hurt you”; and ke’sa’lul means “I put you into the fire.” Those three meanings inform the structure of Thomas’ collection of poetry of the same name and in the film.

Joline first worked with Thomas as a voice for a CBC piece called Words Matter. With additional footage and funding, Joline grew the idea into featuring Thomas in I Place You Into The Fire.

Joline chose all Indigenous illustrators to provide animation of three poems that are woven into the interviews with Thomas in the film—Pauline Young, Christopher Grant and Phyllis Grant, whose traditional illustrations “provided a poignant counterpoint to the contemporary themes,” said Joline.

As the documentary took shape, it became a celebration of Indigenous creativity and resilience. “When artists come together, the results can be truly extraordinary, touching hearts in unexpected ways," Joline said.

Personal storytelling

Writing about family stories includes deeper reflection on the ownership of those stories. Thomas discussed this with Windspeaker.com, explaining her thought process around navigating family members and their reactions to her sharing family histories and her experiences within those stories.

If a story has deeply affected her, Thomas said she has “the right to talk about it, even if it involves other people.”

It’s important when using personal stories as teaching tools that audiences know Indigenous peoples’ stories are unique, and knowing one family’s story should not be assumed to represent others.

As Thomas explained, she is “just one Indigenous person in a collective of millions across Turtle Island,” she said. “My truth and story is not the truth and story of Indigenous peoples. I can point towards trends, collective experiences of many, but not all. We're not a monolith.”

Thomas sees herself as the adult version of a “scrappy kid that grew up off reserve with a parent that went to residential school.”

When bringing in Indigenous academics or Indigenous knowledge keepers or artists, she said, it’s very important to recognize that “we all come from very different backgrounds, experiences, given our nations, our histories and our personal experience.”

Accountability and acceptance

Thomas’ themes of accountability and acceptance also require a thoughtful reflection of where we, the audience, and where our society is at in this time.

“We see often that the more official something becomes, like reconciliation—oh, Canada's working on reconciliation—then the less the individual feels that they have a responsibility to do something,” said Thomas in the film. “And I think that that can be inherently problematic as well.”

When it comes to accountability, there can be discomfort or reactive rejection.

In I Place You Into The Fire, Thomas invites us to consider that “accountability doesn't always have to be aggressive and hard and awful.”

“Accountability can be an acceptance of the current reality that you played a role in getting to, and then choosing from the myriad of pathways to go forward,” she said. “You might only think that there's this pathway, but actually there's some over here that we can talk about,” said Thomas.

For example, if someone is born into a more privileged position in this country, in this system, accountability is recognizing that, acknowledging the advantages received and, through that, understanding how others without that privilege were, and continue to be, impacted. Thomas recognizes her own intersections with privilege and uses her roles to speak about how we can all learn more.

“Everybody needs to be accountable to something, and to someone.”

There’s a real risk of performative actions, Thomas said.

“Sometimes I get sick and tired of talking about truth and reconciliation because I think it’s just been watered down so much and becomes such a buzzword that it's lost all meaning.

“I don't care if I ever see another orange shirt or a flag at half-mast. If there is no meaningful action behind those symbols, then it's not good enough,” she says in the film. “I would much rather see action than symbolism because we're beyond that.”

Role of Artists

This is where artists come in, with the ability to challenge the status quo and speak out without fear of repercussions, Thomas told Windspeaker.

Artists have the power to challenge societal norms and institutions, even when those in positions of power may be resistant to change. Through their creative expressions, artists can provoke thought, evoke emotion and inspire action, ultimately contributing to broader social and political discourse.

As the poet laureate of Halifax for 2016 to 2018, she witnessed the power of artistic expression on shaping public consciousness towards tangible change. Her poem Not Perfect helped lead to the removal of a controversial statue of Edward Cornwallis from a city park. Calls for its removal had been ongoing, as Cornwallis is known for proclaiming an extirpation of Mi’kmaq peoples. In 1749 he issued an order that came to be known as the Scalping Proclamation. His government would pay a bounty to anyone who killed a Mi’kmaq adult or child.

"I'm asking for your help to heal generations of spiritual welts because we were seen as animals only valued for our pelts," wrote Thomas.

She emphasizes the power of artists to challenge societal norms and effect change, saying, "I think artists have a role to challenge a populace and challenge people in positions of power without having to worry about whether or not they'll be re-elected or whether or not they'll lose their jobs, because they are able to be artists and they make their own jobs."

While Thomas said she sometimes writes for specific audiences, she mostly writes in the hopes of being understood.

Her writing process can be both structured and spontaneous and, similarly, the documentary moves from deliberate discussions to capturing spontaneous moments that synchronize with the themes.

There’s a scene in the film where she’s discussing how she learned patience, kindness and doing things “because they’re the right thing to do” from her grandfather, and her dog comes to her side to comfort her. She pets him, letting him know she appreciates the empathy. The moment throws the wounds, the healing, and her choice to move forward into fine focus.

As an artist, Thomas is inspired by the capacity of art to foster empathy, connection and understanding among individuals. The film does this by exploring the complexity and universality of human experiences, from familial relationships to broader themes of identity and belonging.

"I just want people to see the humanity in us as Indigenous people, or as a person who grew up with a family that wasn't perfect or that had a bunch of flaws. To see the humanity and the good and the worthiness and also the beautifully mundane that exists in our worlds too."

The visual art and animation in the film combines with the storytelling to evoke emotions and prompt reflection, generating a sense of shared humanity and empathy.

Joline is also working on a series of documentaries about Indigenous women in Atlantic Canada called Women of This Land. Thomas has an upcoming book called Grampy’s Chair, a children's picture book that honours her relationship with her grandfather. llustrations by Coco A. Lynge, who is Inuk from Greenland.

See I Place You Into The Fire at the Reel 2 Real Film Festival for Youth in Vancouver, which runs from April 7 to April 16. Visit here for more information. Public showing on Sunday, April 14 at 10 a.m. Details at https://r2rfestival.org/production/i-place-you-into-the-fire/

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.