Image Caption

{ALBUM_998677}

By Barb Nahwegahbow

Windspeaker.com Contributor

TORONTO

Chief Stacey LaForme wasn’t prepared for the intense emotion he felt when he walked into Anishinaabeg: Art & Power, the exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that opens on June 17 in Toronto.

“Powerful is the only way I can describe it to you,” said Chief LaForme of Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation to the 200 people gathered at the Community Opening reception for the exhibition.

“When I walked in there, I felt such intense power from it. You’re immediately transported back to old days. You’re immediately reminded of your connection to your history and your culture.”

The breadth, scope and beauty of the work is awe-inspiring as evidenced by the reactions of people who attended. The exhibit runs until Nov. 19 and is a celebration of the beauty, power and passion of Indigenous art.

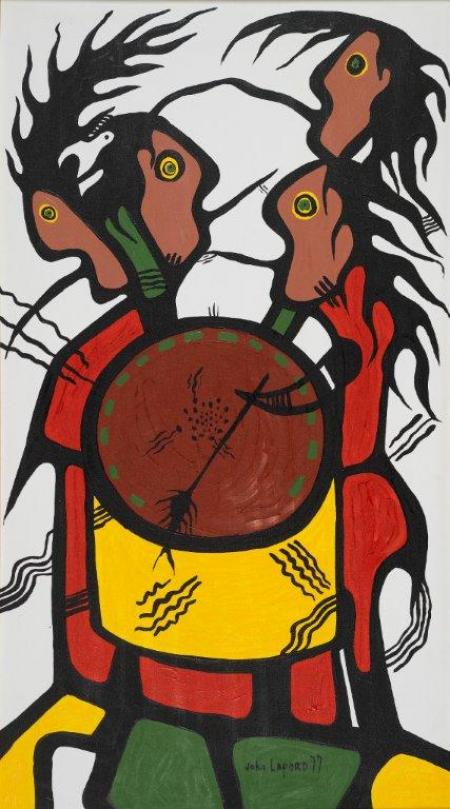

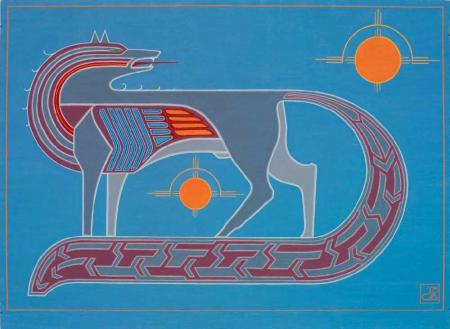

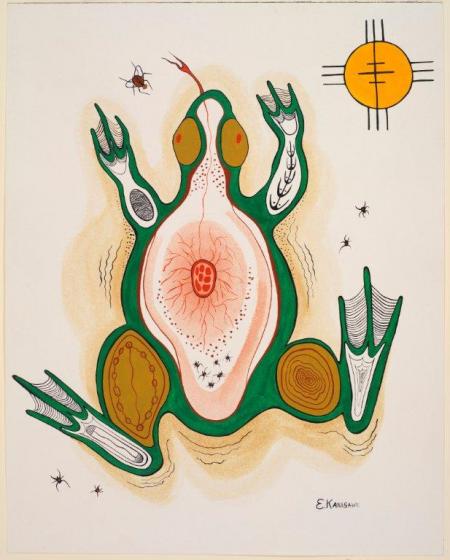

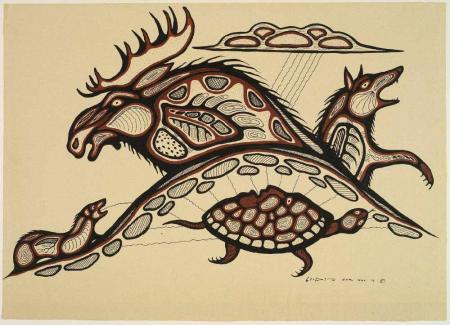

It explores the history, traditions and legends of the Anishinaabeg through several hundred years of their art. It primarily focuses on Anishinaabeg beadwork and paintings of the Woodlands School.

Anishinaabeg: Art & Power was developed by three curators – Arni Brownstone, who has been with ROM since 1972, and two guest curators, Alan Corbiere and Saul Williams.

Corbiere is a historian from M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island. Williams, from North Caribou Lake First Nation in northern Ontario, is a painter and a member of the Woodlands School of Art. The show was initially just to include Woodlands School paintings, said Corbiere, but expanded to include beadwork, sculptures, pipes, drums, birchbark scrolls and a syllabics scroll.

The Woodlands School, well-known through the work of Norval Morrisseau, blossomed in the early 1970s. Through their paintings, Morrisseau and later artists shared the Anishinaabeg beliefs and traditions that had gone underground for many centuries, because of persecution by the state and church.

Brownstone said they sorted through 700 paintings and selected 25 for the exhibition.

Included are early paintings of Morrisseau done on kraft paper, as well as works by Carl Ray, Blake Debassige, Francis Kagige, Richard Bedwash, Daphne Odjig, Del Ashkewe, Jackson Beardy and Roy Thomas, among others.

Kathryn Wabegijig of Garden River First Nation has a piece entitled, “Self Portrait in Reclaimed Copper” with the artist’s silhouette done in copper pennies hammered to obliterate the Queen’s face. Wabegijig has portrayed herself as though framed in a Canadian penny.

The beadwork in the exhibition dates from 1875 to 1925. A favourite piece of Chief LaForme’s is a Ceremonial Shirt collected in 1890 by the Indian Agent at Turtle Mountain, North Dakota.

One of the themes of the exhibition is the way that Anishinaabeg art changed as they moved and intermingled with other nations. The woolen shirt shows the changes in dress clothing that came about when the Anishinaabe moved west and were influenced by their prairie neighbours.

Some of the beadwork is Plains geometric beadwork, but some of it remains true to Anishinaabeg designs.

Urban Indigenous youth were uppermost in Corbiere’s mind when he was curating. These kids may never get the opportunity to see these things, he said. “They’ll maybe see pipes, but they won’t see the magnificently sculptured pipes on display here. And maybe they have an app that shows syllabics, but here they’ll see a piece of birchbark painted with syllabics.”

Corbiere has a favourite piece in the show, a small wooden statue cloaked in snakeskin carved circa 1700s by Chief Pitwegijig of Walpole Island. It was used to make sacred offerings. It’s fascinating, said Corbiere because it’s a symbol of our endurance but also of religious persecution and colonization.

When the Jesuits arrived at Walpole Island in 1844, said Corbiere, “they began cutting down trees to build a church having obtained permission from the Governor and the Indian Agent.

The Jesuits had not consulted with the chiefs who told them to stop. A debate ensued but the Jesuits carried on. Within a week of finishing the church, it was burned to the ground and Chief Pitwegijig was the main suspect.

In 1870, the chief was converted to Christianity and became Anglican at which point he gave the deity figure to the Anglican priest’s wife.

“It’s the story of what we went through in just one item,” said Corbiere, and he hopes it sparks important conversations.

Artist and co-curator Saul Williams said that he was born into art and lives with art.

“I love what I paint,” he said, “and what I tell in my stories, those are values and practices of my people.” His first experience with art was seeing the rock paintings in his area, he said, “and that’s how I began painting.”

Williams has a piece in the exhibition titled, “White Women and Their Plants.”

“When I first came to Toronto in 1972,” Williams said, “and those kind people took me into their homes…what I noticed in most houses was there was plants, all kinds of things growing inside. But back home in my mother’s house, you wouldn’t see that. You would see tools like axe or snares, traps, or clothes drying, snowshoes. But you wouldn’t see plants. You wouldn’t see flowers.”

This observation about cultural difference inspired him to create the piece in the show. “I like telling stories with my art,” Williams said, “I paint what I see.”

Arni Brownstone said this show is distinctive in that it takes into account the fact that the Anishinaabeg “lived in a multi-ethnic environment for many years before the Europeans came and intermingled. What happens to the art? What happen as a result of that cultural interface? That’s one of the things this exhibition emphasizes that I think is unusual.”

ROM Director and CEO Josh Basseches said Anishinaabeg: Art & Power is, “an exhibition unlike any this museum has seen.”

This collection, he said, has been assembled by passionate Indigenous artists and teachers who are well-positioned to tell the story about their communities.

“Just as important as the stories we tell are those who do the telling,” said Basseches. The Truth and Reconciliation Report presents both a challenge and a great opportunity, he said, “to change how we share the stories and objects of the First Peoples whose cultures precede the founding of this nation by centuries.”

The ROM offers free admission to Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. This offer includes the exhibition Anishinaabeg: Art & Power but does not apply to special programs, annual memberships, or surcharged exhibitions.